Strength Reduction

Compilers perform many optimizations to improve performance, and among these is strength reduction. Strength reduction is an optimizations by which a compiler replaces expensive operations with less expensive ones that produce a functionally equivilant result. In this blog post, we’ll be taking a look at how strength reduction can be used to replace expensive operations like idiv with various other arithmetic operations, as well as looking at the difference in performance.

Links

- My Strength Reduction Video

- My YouTube Channel

- My GitHub Account

- My Email: CoffeeBeforeArch@gmail.com

Strength Reduction of Integer Division

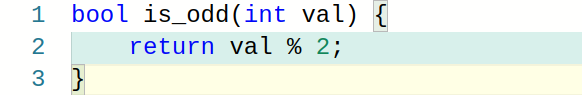

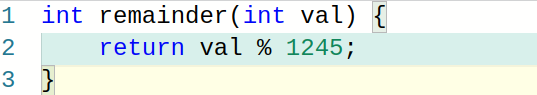

Division instructions are expensive. However, your compiler can play some tricks to get around them. Let’s start by taking a look at a simple is_odd function on Compiler Explorer. One way we can implement this function is with the modulo operator. We can do modulo 2 in order to get the remainder when dividing our input value by 2. Let’s see how this looks in C++.

Now lets look at the assembly generated for this function.

Our compiler was pretty clever! Instead of using an expensive idiv, our compiler used a bitwise AND instruction by 1. This checks if the least significant bit of an input is set (allowing us to check if the number is odd). Pretty neat! However, checking if a number is odd is rather trivial. Let’s give our compiler a more difficult problem.

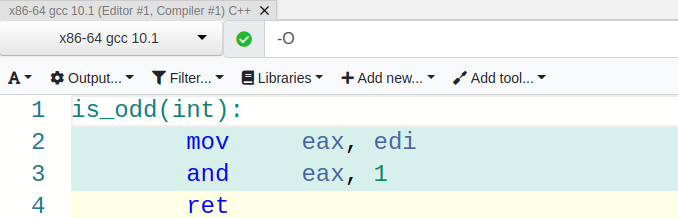

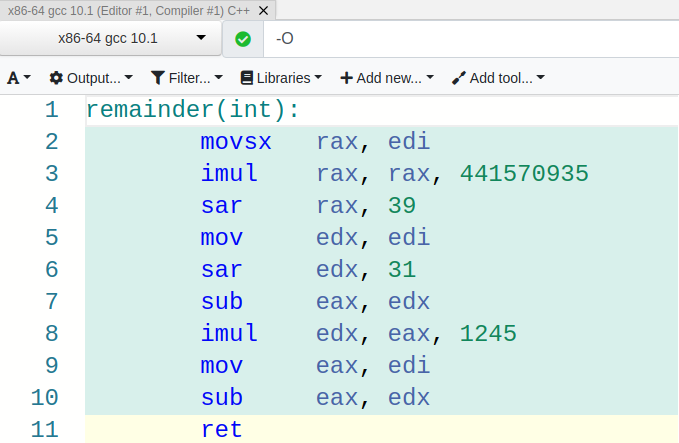

Let’s transform our is_odd function into one called remainder that returns the remainder when the input is divided by some constant (1245 in this case). Here’s what that may look like in C++.

Now let’s take a look at the assembly.

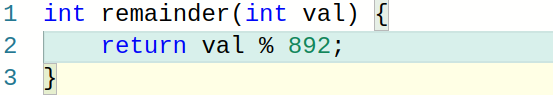

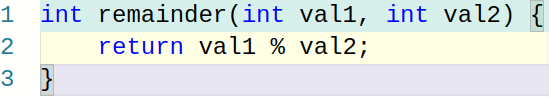

Looks like our compiler found a way around using an idiv instruction again! This time, it used a combination of shifts, multiplies, subtracts, etc. to functionally replace the expensive division instruction. Let’s try another value (892) to see what the assembly looks like (in case we just got lucky with 1245). Here’s the high-level C++.

And here is the assembly.

Looks like we got a similar output! The compiler found another combination of arithmetic operations (outside of division) to replace the idiv instruction.

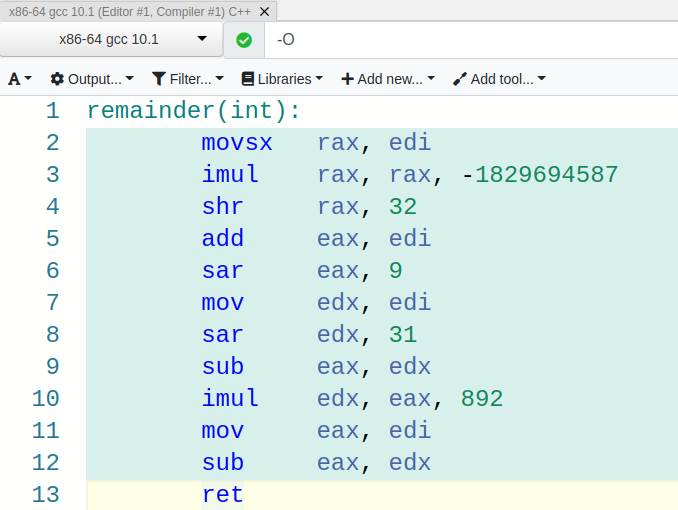

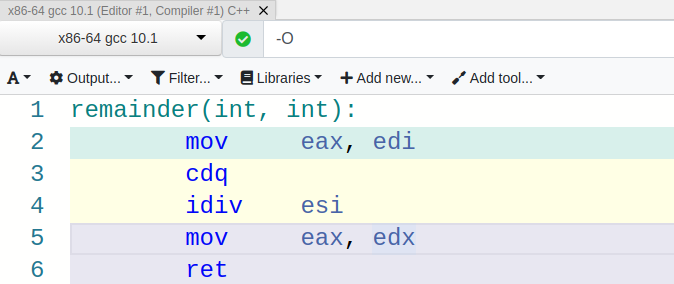

Here’s a good question. When can’t the compiler replace the idiv instruction in some clever way? One obvious reason why a compiler may not be able to get rid of a division instruction is if we aren’t doing modulo by some constant known at compile-time. If the compiler doesn’t know the value we’re doing modulo by, it has to be conservative, and generate code that works in all possible cases. Let’s replace the constant we’re doing modulo by a second input to our function. Here’s the C++ with those changes.

And here is the corresponding assembly.

No strength reduction! We get the expected idiv instructions.

Benchmarking Strength Reduction

Are all the extra instructions really worth it? Let’s benchmark it and find out! Here’s a benchmark for the strength reduction implemenation.

static void srMod(benchmark::State &s) {

std::vector<int> v_in(4096);

std::vector<int> v_out(4096);

for (auto _ : s) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < v_in.size(); i++)

v_out[i] = v_in[i] % 1245;

}

}

BENCHMARK(srMod);

And here is the corresponding assembly.

0.17 │120:┌─→movslq (%r8,%rcx,4),%rax ▒

28.65 │ │ mov %rax,%rdx ▒

0.39 │ │ imul $0x1a51d677,%rax,%rax ▒

│ │ mov %edx,%esi ▒

│ │ sar $0x1f,%esi ▒

33.86 │ │ sar $0x27,%rax ▒

0.21 │ │ sub %esi,%eax ▒

0.95 │ │ imul $0x4dd,%eax,%eax ▒

1.12 │ │ sub %eax,%edx ▒

34.62 │ │ mov %edx,(%r9,%rcx,4) ▒

0.02 │ │ inc %rcx ▒

│ ├──cmp %rcx,%rdi ▒

│ └──jne 120

No division instruction! Here is our baseline benchmark using that uses the division instruction.

static void baseMod(benchmark::State &s) {

std::vector<int> v_in(4096);

std::vector<int> v_out(4096);

for (auto _ : s) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < v_in.size(); i++)

v_out[i] = v_in[i] % s.range(0);

}

}

BENCHMARK(baseMod)->Arg(1245);

And here is the corresponding assembly.

│120:┌─→movslq (%r9,%rcx,4),%rax ▒

0.11 │ │ cmp %rsi,%r8 ▒

│ │↓ je 144 ▒

│ │ cqto ▒

96.39 │ │ idivq (%rsi) ▒

0.09 │ │ mov %edx,(%r10,%rcx,4) ▒

│ │ inc %rcx ▒

│ ├──cmp %rdi,%rcx ▒

3.40 │ └──jne

We’re able to avoid the compiler’s strength reduction optimization by hiding the constant value of 1245 behind a layer of indirection (passing it as an input argument).

We can use the following compiler command to build our benchmarks. I’ve left the optimization level at O2 to prevent vectorization in the strength reduction benchmark (since our division benchmark will not be vectorized). Alternatively, you could use O3 with the flag -fno-tree-vectorize.

g++ mod_bench.cpp -lbenchmark -lpthread -O2 -march=native -mtune=native -flto -fuse-linker-plugin

And here are the results from our two benchmarks (respectively).

-------------------------------------------------------

Benchmark Time CPU Iterations

-------------------------------------------------------

srMod 4.62 us 4.61 us 151354

baseMod/1245 36.3 us 36.3 us 19201

Almost 9x faster! Using strength reduction. There are a few reasons for this. For one, division is just a slow operation. There is also limited hardware for division on chip because division is a less freqently performed operation. Having a greater number of instructions to choose between in the strength reduction benchmark also improves instruction-level parallelism (ILP).

Concluding Remarks

You should generally trust your compiler to perform optimizations like strength reduction. Performance is non-intuitive! More instructions does not necessarily mean slower code! Compiler writers spend a lot of time designing these optimizations, and won’t enable them automatically if they would hurt performance. If you’re skeptical, benchmark and find out!

As always, feel free to contact me with questions.

Cheers,

–Nick

Links

- My Strength Reduction Video

- My YouTube Channel

- My GitHub Account

- My Email: CoffeeBeforeArch@gmail.com