Aliasing

Compilers can do a great job at optimizing our programs. However, there are limitations on what a compiler can do, given limited information. One limitation that can prevent a number of optimizations is aliasing. If a compiler can not tell if two pointers (or references) refer to the same location, you may miss out on vectorization, and incur extra loads and stores. In this tutorial, we’ll be looking at aliasing from a back-to-basics standpoint.

Links

- My YouTube Channel

- My GitHub Account

- My Email: CoffeeBeforeArch@gmail.com

Aliasing - A Simple Example

A video version of this section can be found here.

Let’s consider a very simple function called add, that takes two integers by reference, sets each to a value, and returns their sum. Let’s first set our input references a and b to the same value, and return their sum.

// add.cpp

int add(int &a, int &b) {

a = 5;

b = 5;

return a + b

}

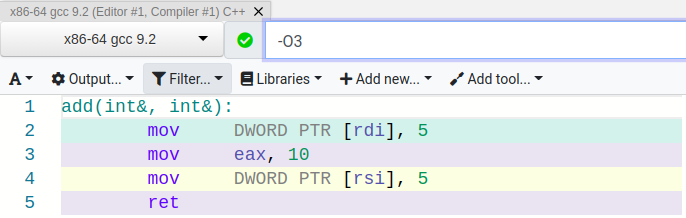

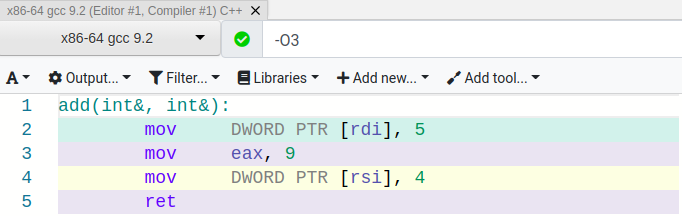

I like to use Compiler Explorer to look at source and assembly side-by-side. Here is my results with O3 optimizations enabled.

Nothing terribly surprising in the output, and the compiler seems to perform the optimizations we’d expect. The value of memory locations a and b are set to 5, and their sum is precomputed. Simple enough. Now let’s see what happens if we change a and b to be different values.

// add.cpp

int add(int &a, int &b) {

a = 5;

b = 4;

return a + b

}

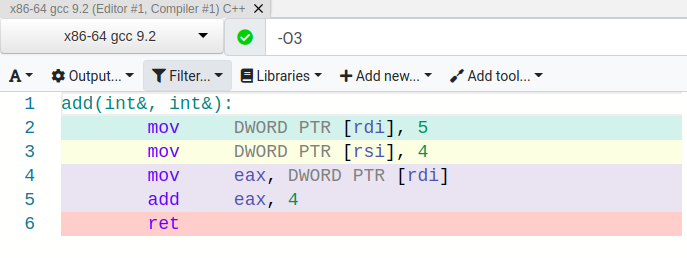

Two major things seem to have happen. For one, we lost our precomputed result. Second, we seem to be loading a into the eax register after setting it. Why did these things happen? Aliasing! The compiler does not have enough context to determine if a and b refer to the same location in memory. As a result, the compiler must be conservative, and assume that they could point to the same memory location. Let’s consider a simple example of why the compiler must make this decision.

Imagine the following call to our add function that sets a and b to different values.

int a = 2;

int b = 3;

int result = add(a, b);

The final value of result should clearly be 9 (just the simple addition of 5 + 4). It seems simple enough to precompute the value. However, consider this slightly different call.

int a = 2;

int result = add(a, a);

This is a perfectly valid way to call the function, but what should the result be? 8, not 9! Inside the add function, the input parameters a and b refer to the same piece of memory. When we set a to 5, b is also being set to 5. Likewise, when b is set to 4, a is also set to 4. That means precomputing a result of 9 can lead to an incorrect result, depending on the input.

Now let’s think about two things. First, why was the result precomputed when we set a and b to the same value, despite the fact we know the function suffers from aliasing? This is because the result would be the same regardless of a and b aliasing each other or not (they will always be set to the same value).

Second, what is the assembly doing in the case where a and b are set to different values? First, a and b are set to 5 and 4 respectively. Then, because the store into b could have updated a (the case where a and b alias each other), we reload a from memory. Then, we add 4 to a, which was previously loaded into the eax register. Because we know the value of b must be 4 (because it was the last memory address stored to), the compiler opts to use an immediate value 4, rather than reloading b from memory.

Now let’s modify the add function input to take an integer and a floating point number.

// add.cpp

int add(int &a, float &b) {

a = 5;

b = 4;

return a + b

}

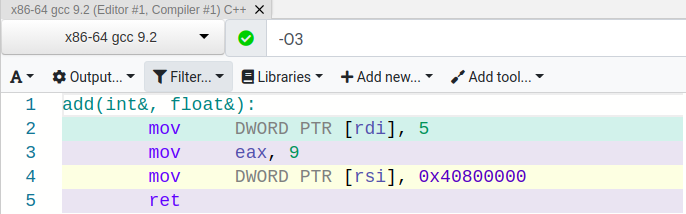

Now let’s take a look at the assembly generated:

Our optimizations came back! But why? This can be attributed to a thing called type-based alias analysis. Different types are not always allowed to alias each other. This is the case for integers and floating point numbers. Because the compiler knows about these rules, it can precompute the return value, as it did when a and b were set to the same value.

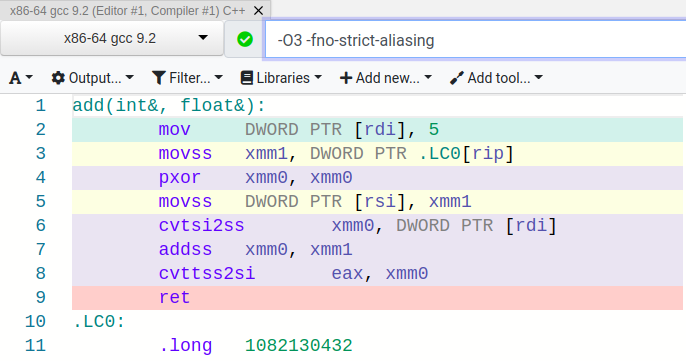

But what if we disabled those rules? Let’s see what happens if we add the compiler flag -fno-strict-aliasing, allowing the compiler to thing that an integer and floating point number can alias each other.

Yikes! Functionally, this does the same thing as the aliasing case for two integers. The only major difference is that we have to extra instructions to convert between integer and floating point numbers (e.g., cvtsi2ss and cvttss2si).

Ok, so now we have some insight into aliasing, and how it can lead to less optimal code. Let’s take a step back and discuss how we can solve this problem with our original add funcion. In the programming language C, we can solve this problem by adding the restrict qualifier to our references. This is just a hint to the compiler that pointers or references will not alias each other. Fortran solves this problem by simply not allowing parameters to be aliases. But what about C++?

C++ does not have a restrict keyword. However, most every major compiler supports an intrinsic to say that references or pointers do not alias each other. In the case of gcc, we can use __restrict. Here’s our modified add function.

// add.cpp

int add(int& __restrict a, int& __restrict b) {

a = 5;

b = 4;

return a + b

}

Let’s see what happened in the resulting assembly.

Our optimizations came back! The compiler just needed a little extra information to provide us with the optimal code!

Aliasing - Matrix Multiplication (CPU)

A video version of this section can be found here.

Now that we have a better foundation on aliasing, let’s see how it can affect something like vectorization. For this we’ll be taking a look at a simple matrix multiplication function. The source code for the following examples can be found here.

Here is a naive implementation of matrix multiplication using a triply-nested for loop.

void base_mmul(const int *a, const int *b, int *c, const int N) {

// For every row...

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

// For every col...

for (int j = 0; j < N; j++) {

// For each element in the row-col pair

for (int k = 0; k < N; k++) {

// Accumulate the partial results

c[i * N + j] += a[i * N + k] * b[k * N + j];

}

}

}

}

In our first example, we’ll have this, and the rest of our benchmark in a single cpp file. Let’s compile it with the following command.

g++ single_tu_bench.cpp -lbenchmark -lpthread -O3 -march=native -mtune=native -o single

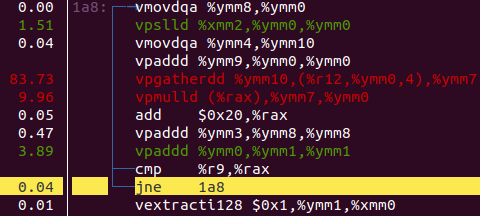

Using some simple profiling with perf record and perf report, we can see where we’re spending time in our benchmark.

We seeme to be clearly bottlenecked on a gather instruction, but that is a problem for another time. What we will focus on is the fact that the compiler seems to have used a lot of vector instructions to implement matrix multiplication.

Now let’s compile our matrix multiplication function separately, and link it with the rest of the benchmark code. The code was compiled using the following commands.

g++ -c base_mmul.cpp -O3 -march=native -mtune=native

g++ multi_tu_bench.cpp base_mmul.o -lbenchmark -lpthread -O3 -march=native -mtune=native -o multi

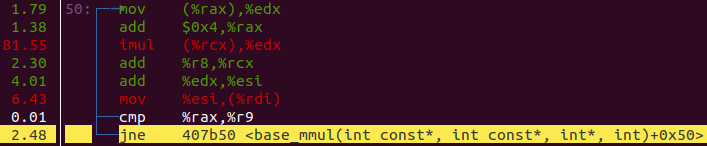

When we profile this code using perf record and perf report, we see the following hotspot.

Our vectorization went away! But what happened? Our matrix multiplication and benchmark code is identical to the first example, but is now compiled in different translation units. Let’s think back to earlier when we discussed alias analysis and context.

When we compile our matrix multiplication code with the rest of the benchmark in the same translation unit, the compiler can determine that the pointers passed in the call to base_mmul are not aliases of each other, and optimize the function accordingly. However, when base_mmul is compiled separately from the call-site, this analysis and extra optimization is not done by default during linking.

However, at the cost of some longer build times, we can enable something called link-time optimization. This helps catch some of the interprocedural optimizations that have been missed because code was compiled in separate translation units. Let’s rebuild our mutli-translation unit code with the -flto flag to enable this.

g++ -c base_mmul.cpp -O3 -flto -march=native -mtune=native

g++ multi_tu_bench.cpp base_mmul.o -lbenchmark -lpthread -O3 -flto -march=native -mtune=native -o multi

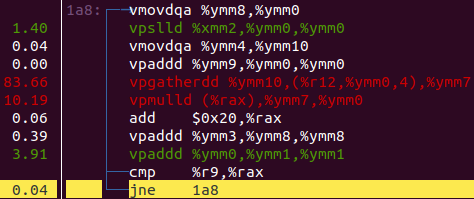

Re-profiling the code with perf record and perf report shows the following.

Our vectorization came back! So how does link-time optimization work? At compile time, the compiler writes the internal representation into the output file, delaying some optimization. At link time, when the full context of the program is known, optimization across translation units can be performed, which can result in significant speedups (depending on the applicaiton).

Aliasing - Matrix Multiplication (GPU)

Aliasing can also be an issue for CUDA kernels that run on NVIDIA GPUs. Let’s take a look the simple version of matrix multiplcation kernel shown below.

__global__ void matrixMul(const int *a, const int *b, int *c, int N) {

// Compute each thread's global row and column index

int row = blockIdx.y * blockDim.y + threadIdx.y;

int col = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

// Iterate over row, and down column

c[row * N + col] = 0;

for (int k = 0; k < N; k++) {

// Accumulate results for a single element

c[row * N + col] += a[row * N + k] * b[k * N + col];

}

}

Each thread simply performs the dot product of a single row and column from matrices a and b respectively, and stores the result to the output matrix c. The full code can be found here. Let’s go ahead and compile the program using the following command.

nvcc matrixMul_naive.cu -O3 -o mmul

For square matrices a, b, and c, with dimension N = 2^10, the execution time I recorded for this kernel was ~3.45ms. Let’s take a look at an alternate implementation of matrix multiplication (located here).

__global__ void matrixMul(const int *a, const int *b, int *c, int N) {

// Compute each thread's global row and column index

int row = blockIdx.y * blockDim.y + threadIdx.y;

int col = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

// Iterate over row, and down column

int tmp = 0;

for (int k = 0; k < N; k++) {

// Accumulate results for a single element

tmp += a[row * N + k] * b[k * N + col];

}

// Write back the result

c[row * N + col] = tmp;

}

The only major difference in the source code is that instead of directly accumulating into the c matrix, we use a temporary variable (tmp). Let’s re-compile with the following command, and measure the execution time.

nvcc matrixMul_alt.cu -O3 -o mmul

On the same GPU with the same input size, I measured ~1.23ms. This is over almost 3x faster than the other version! What happened? Well, let’s take a look at some other statistics for these programs. Specifically, let’s look at the number stores that the program performs. We’d want this number to be low, as our program should be load-heavy. The only real stores we need are to write back the accumulated partial results to the c matrix. Let’s collect the L2 write transactions and see.

For the first implementation (without the temporary variable), I recorded 134,348,816. For the implementation with the temporary variable, I recorded 131,088. That’s over 1000x fewer transactions! Let’s take a look at the assembly to see what happened.

In the version with the temporary variable, I find only a single store at the end of the assembly, writing the accumulated result stored in R27 into the c matrix

/* 0x000fe40007ffe0ff */

/*0e10*/ MOV R3, 0x4 ; /* 0x0000000400037802 */

/* 0x000fca0000000f00 */

/*0e20*/ IMAD.WIDE R2, R2, R3, c[0x0][0x170] ; /* 0x00005c0002027625 */

/* 0x000fd400078e0203 */

/*0e30*/ STG.E.SYS [R2], R27 ; /* 0x0000001b02007386 */

/* 0x000fe2000010e900 */

/*0e40*/ EXIT ; /* 0x000000000000794d */

The assembly from our original code that does not use temporaries shows a very different story. Without posting the entire code, the highlight is that we first see the store that zeroes out elements in the c matrix.

/*00e0*/ STG.E.SYS [R2], RZ ; /* 0x000000ff02007386 */

Afterwards, there are multiple stores to the same address address of the c matrix stored in R2, writing back partial results.

/*0290*/ STG.E.SYS [R2], R5 ; /* 0x0000000502007386 */

Aliasing again! The compiler can not determine if a, b, and c alias each other. This means that the compiler has to assume that when we write to c, we could also be writing to a or b as well (if they are aliases). This keeps the compiler from optimizing away the majority of the stores to register writes.

Why didn’t this occur in the version with the temporary variable? When we declare that variable tmp it is located on the stack, in private per-thread local storage. The compiler can fairly easily decide to just place this inside of a register (R27 in this case). This private storage can not possibly alias the other global memory pointers (it’s private to this thread!).

Fortunately, we can give the compiler some extra help. Just like we did with our simple add function, we can use the __restrict intrinsic to inform the compiler that our pointers are not aliases of each other. The full code can be found here

__global__ void matrixMul(const int* __restrict a, const int* __restrict b, int* __restrict c, int N) {

// Compute each thread's global row and column index

int row = blockIdx.y * blockDim.y + threadIdx.y;

int col = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

// Iterate over row, and down column

c[row * N + col] = 0;

for (int k = 0; k < N; k++) {

// Accumulate results for a single element

c[row * N + col] += a[row * N + k] * b[k * N + col];

}

}

We can compile the code using the following command

nvcc matrixMul_naive.cu -O3 -o mmul

Measuring the execution time, we find huge improvement over the orignal code, and a result very close to the version using the temporary variable (~1.23ms for the kernel with 262,160 L2 write transactions). Looking at the assembly, we find only 2 stores! The first corresponds to the zeroing out of the element of the c matrix.

/*00e0*/ STG.E.SYS [R2], RZ ; /* 0x000000ff02007386 */

The other store is writing back the final result that was accumulated in R27.

/*0e00*/ STG.E.SYS [R2], R27 ; /* 0x0000001b02007386 */

All the compiler needed was a little help in order to provide the optimizations we manually added with a temporary variable!

An interesting question here is, why did we still have an aliasing problem when the CUDA kernel and launch code are located in the same file, and seemingly same translation unit? The answer likely is in the fact that there are multiple compilers at work here! The host code on my machine is getting compiled with gcc on my machine, and the CUDA code by NVCC. As a result, the CUDA code is compiled spearately from the call-site, and the NVCC compiler likely doesn’t receive any hints from the host compiler about the pointers and if they alias each other. Perhaps this kind of heterogeneous optimization would be a good thing to look at in the future.

Concluding Remarks

One of the most important lessons to learn how decisions made at a high level translate through the compiler into the low-level assembly that actuall executes. While compilers are smart, and can perform complex interprocedural optimizations that a human can’t see, they aren’t omniciant, and need a helping hand here and there.

As always, feel free to contact me with questions.

Cheers,

–Nick

Links

- My YouTube Channel

- My GitHub Account

- My Email: CoffeeBeforeArch@gmail.com