Disabling Asserts

Asserts are a common way to test the functionality of parts of your code, and help with debugging and developing software. However, asserts are not free, and there can be a non-negligable performance increase by simply disabling them in a release build. While this post isn’t to argue that every code base should disable asserts (that depends on your code base, and your situation), it will provide some insights into the type of code that asserts generate.

Links

- My YouTube Channel

- My GitHub Account

- My Email: CoffeeBeforeArch@gmail.com

Background on Asserts

Asserts depend on the macro NDEBUG. We can learn more about this by looking at assert.h, or by the output of the preprocessing step of compiler. Let’s use a simple program to show this (a program that only fails).

// assert.cpp

#include <cassert>

int main() {

assert(0)

return 0;

}

We can get the results of preprocessing using the following command:

g++ -E assert.cpp -o assert.ii

What do we see in the output from preprocessing? Well, we definitely have more code in the *.ii intermediate file (which we should by including other files). The important parts (for this discussion) are the following lines from assert.h…

extern "C" {

extern void __assert_fail (const char *__assertion, const char *__file,

unsigned int __line, const char *__function)

throw () __attribute__ ((__noreturn__));

extern void __assert_perror_fail (int __errnum, const char *__file,

unsigned int __line, const char *__function)

throw () __attribute__ ((__noreturn__));

extern void __assert (const char *__assertion, const char *__file, int __line)

throw () __attribute__ ((__noreturn__));

}

And the replacement of our assert in the main function:

# 3 "test.cpp"

int main() {

# 4 "test.cpp" 3 4

(static_cast <bool> (

# 4 "test.cpp"

0

# 4 "test.cpp" 3 4

) ? void (0) : __assert_fail (

# 4 "test.cpp"

"0"

# 4 "test.cpp" 3 4

, "test.cpp", 4, __extension__ __PRETTY_FUNCTION__))

# 4 "test.cpp"

;

return 0;

}

So what’s going on here? We’re first converting our integral value, 0, passed to the assert to a boolean (True/False) using static_cast<bool>. Based on that result, we either do nothing (the True case that does void (0), or call __assert_fail(...) (the False case).

Now let’s re-do our preprocessing with NDEBUG defined. We could either define it within the *.cpp file, or pass in the compilation flag -DNDEUBG. We don’t need to worry about setting the value of NDEBUG, as the check performed in assert.h is only based on the definition of NDEBUG (#ifdef NDEBUG). Here’s the full preprocessing command:

g++ -DNDEBUG -E assert.cpp -o assert.ii

In our *ii intermediate file, we see far less code included. In fact, we no longer have __assert, __assert_fail, or __assert_perror_fail in the file. If we look at our main function where we called assert(0), we can see the following:

# 3 "test.cpp"

int main() {

# 4 "test.cpp" 3 4

(static_cast<void> (0))

# 4 "test.cpp"

;

return 0;

}

All we see is a cast to a bool (something that will be optimized away by any sane compiler).

Asserts After Compilation

Now that we understand what happens at the preprocessing stage with asserts, we can look more closely at the assembly that gets generated. Let’s take our simple example and look at the result on Compiler Explorer

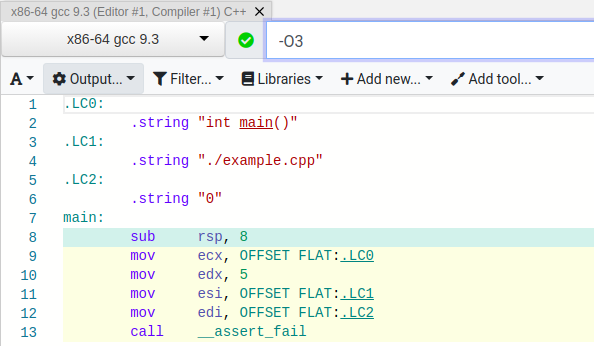

Below we can see the result of compiler our code with g++ with O3 optimizations. Unsurprisingly, we see some the code to setup a call to __assert_fail.

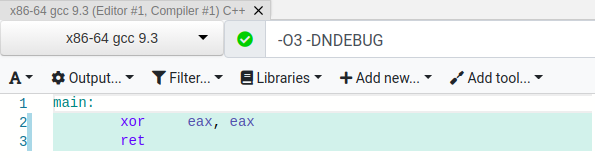

However, when we the DNDEBUG macro is defined (with a compilation flag), our main function simply returns 0 (by zeroing out the eax register).

Ok, so if the compiler can easily tell which branches will be taken, it can reduce the final code to only include that path. Now let’s look at a simple function called test, that takes a value, and makes sure that it equals a certain value (let’s say 2).

#include <cassert>

void test(int val) {

assert(val == 2)

}

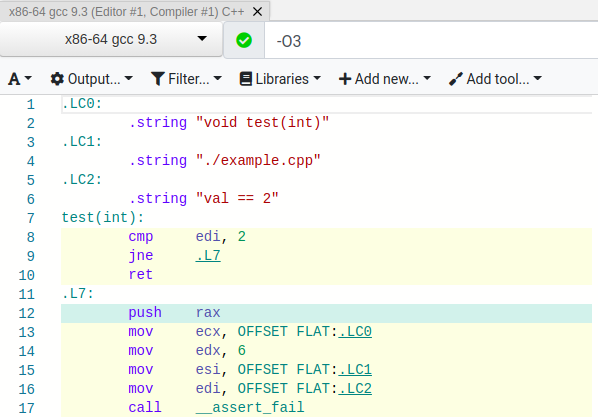

Without any more context, the compiler must generate both code paths (the asserting, and non-asserting paths). We can see that in the resulting assembly.

Even if our program never actually fails the assert, we still pay the price for the comparison and branch. From a performance point of view, what can we say? While this branch should always be correctly predicted, it still takes up space in our instruction cache and pipeline. However, as always, the actual impact on performance depends on the rest of the program.

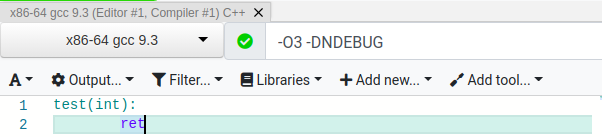

Now let’s see what happens if add -DNDEBUG to the compiler flags.

Our function is completely optimized away! That’s because the preprocessor changes the assert to simply a static_cast<bool>, which effectively does nothing!

Concluding Remarks

As I said in the introduction, disabling all asserts does not make sense for every project. However, it does open the possibilty for further optimization by the compiler. However, this is not a guarantee.

In a previous blog post, I showed a case where removing asserts from led to a 5-15% increase in performance. However, just disabling assertions with -DNDEBUG was not sufficient. While the assertions were removed, the function call used to provide the condition for the assertion remained. As usual, performance is not always intuitive, and you should measure and observe rather than assuming what will work.

As always, feel free to contact me with questions.

Cheers,

–Nick

Discussion Points

-

Why would disabling assertions be a good idea in a release mode? If you have no way to recover from an error to begin with, killing a program with an assertion may not be a useful feature. There’s always a chance that software will still work despite a failed assertion.

-

Why would disabling assertion be a bad idea in a release mode? What if your program could potentially change some permanent state (e.g., update some database, or overwrite some files). Having a program exit if some condition isn’t met could be the right option. However, assertions may not be the correct solution for this case.

Links

- My YouTube Channel

- My GitHub Account

- My Email: CoffeeBeforeArch@gmail.com